Bimaxillary advancement with aesthetic and functional improvement

Traduzione automatica

L'articolo originale è scritto in lingua ES (link per leggerlo).

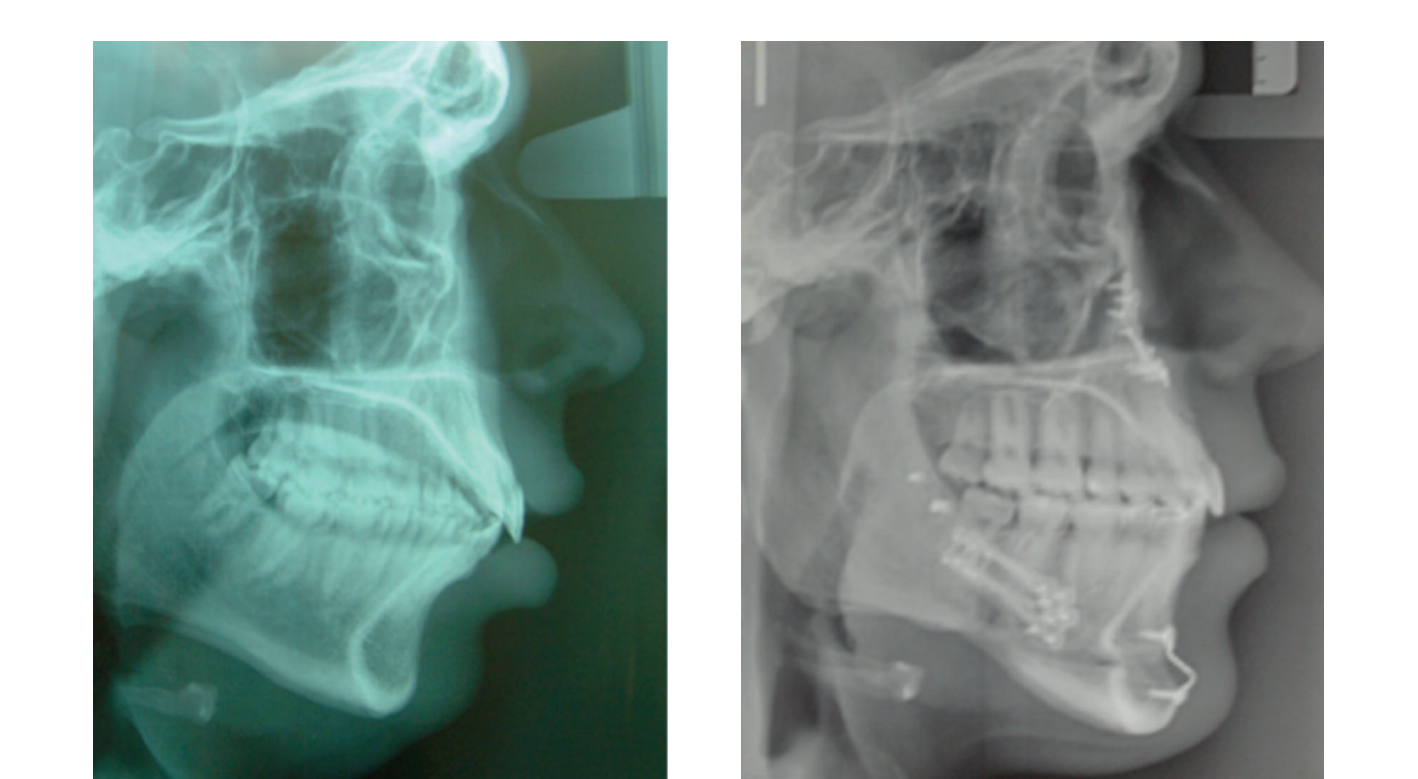

The treatment of dentofacial deformities has evolved significantly in the last ten years. The knowledge of vascular contributions in osteotomies –developed by William Bell–, the versatility of maxillary, mandibular, and chin osteotomies to induce displacements in three-dimensional space, and the use of rigid fixation allow for osteotomies previously considered unstable, such as counterclockwise rotation and/or large maxillary-mandibular advancements.

Advances in digital planning and improvements in anesthetic techniques have allowed orthognathic surgery to develop and simplify significantly.

The goal is no longer just to achieve an adequate and stable occlusion. Our knowledge and the development of these procedures allow us to achieve a dental and occlusal improvement that is stable and has minimal periodontal and/or joint repercussions, but also a significant respiratory improvement and aesthetic goals that are difficult to achieve with other surgical techniques. The predictability of orthognathic surgery is superior to any facial reconstruction technique, as well as its durability.

Class II cases due to mandibular hypoplasia that used to be treated with two upper extractions have benefited from these advances in orthognathic surgery. Thus, our patients are offered much more satisfactory results.

Clinical case

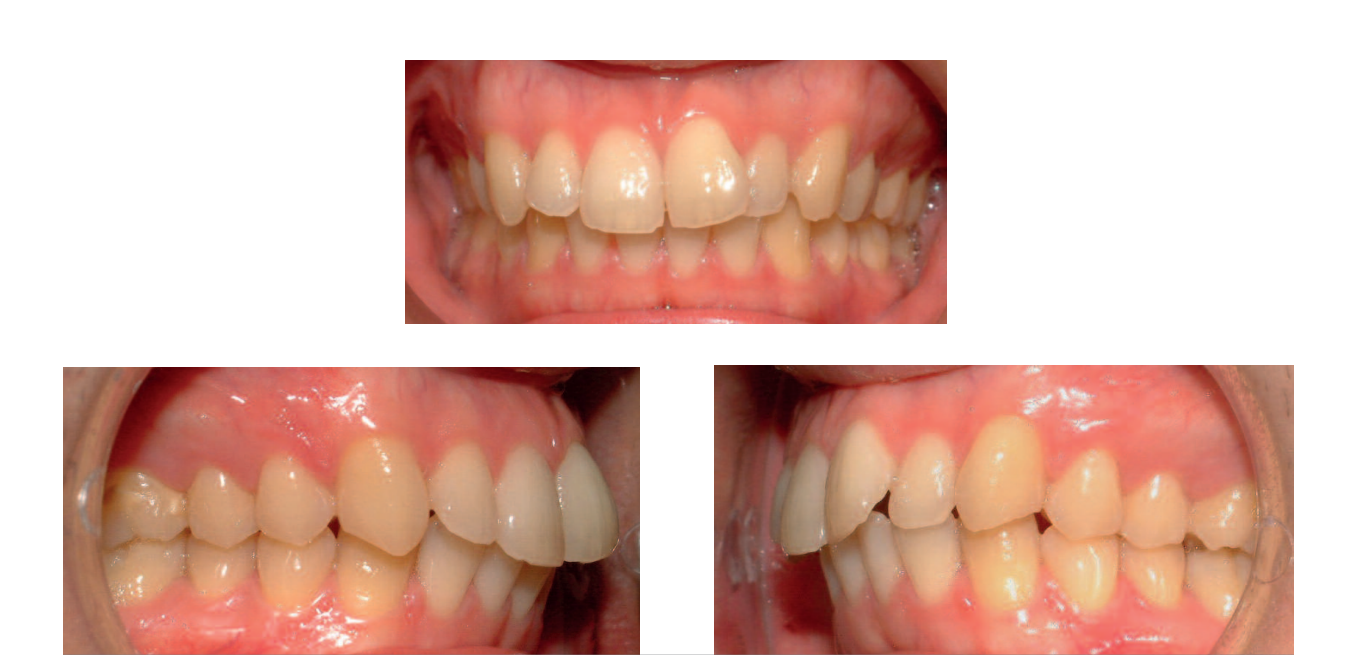

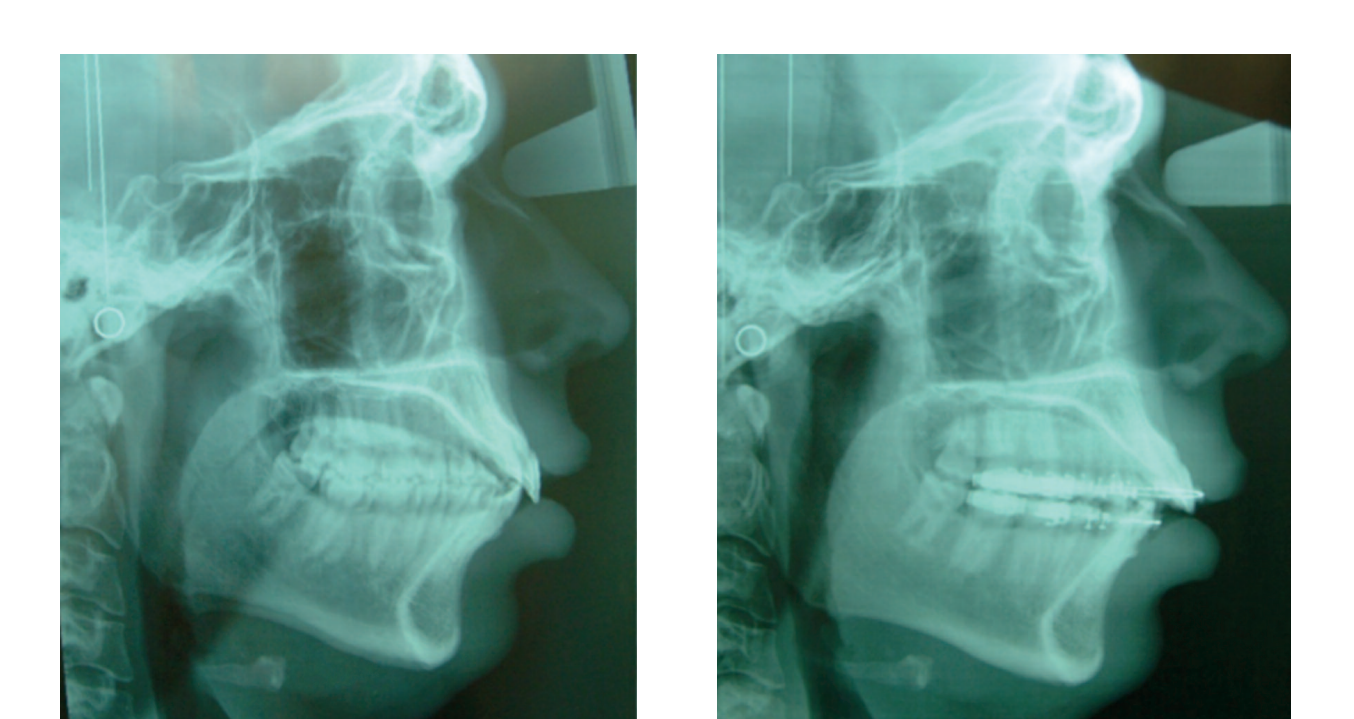

A 20-year-old patient comes to the office for orthodontic evaluation and treatment. Their reason for consultation is a "slight crowding in the upper incisors." After studying the case, we see that we are dealing with a skeletal class II due to mandibular hypoplasia, very dentoalveolar compensated with the protrusion of the lower incisors.

This type of case, in a patient without growth, we used to treat with four extractions to compensate for the class II and the protrusion of the lower incisors.

This orthodontic treatment plan would worsen the lip-tooth relationship, increasing the gingival smile and, of course, would not improve the projection of the lower third, maintaining a retruded mandible.

Advances in current orthognathic surgery mean that orthodontic compensation for class II is no longer our first treatment option, and we approach cases like this from a combined perspective of orthodontics and orthognathic surgery.

Facial analysis

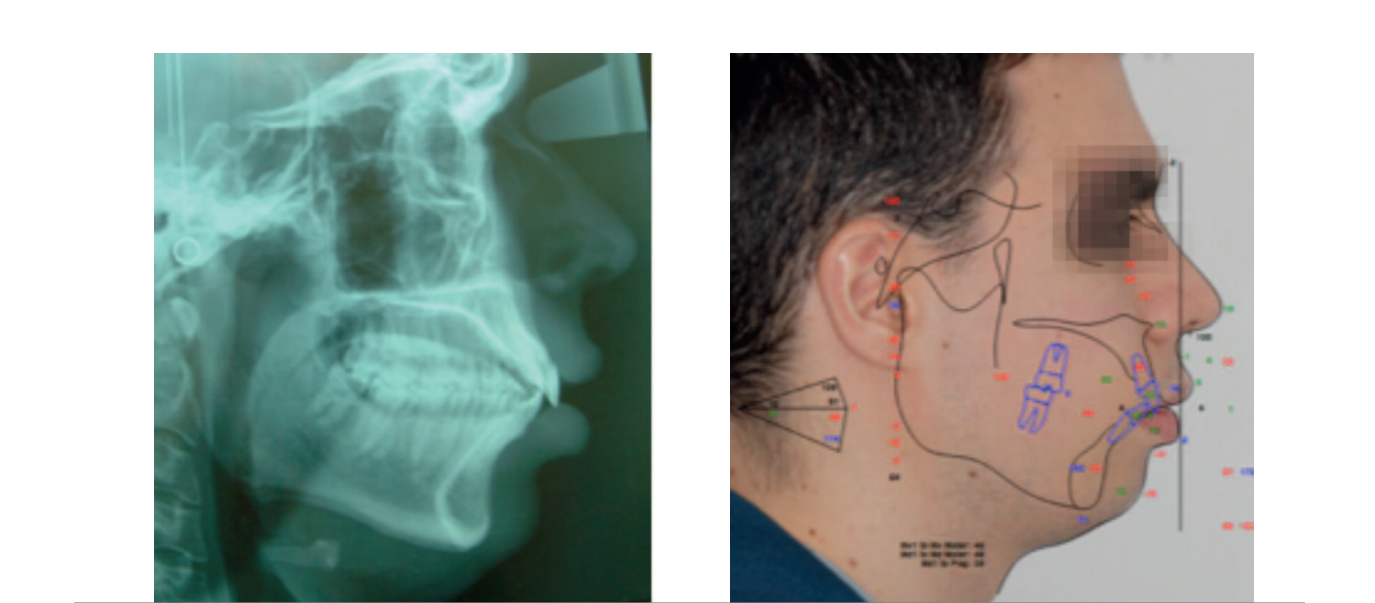

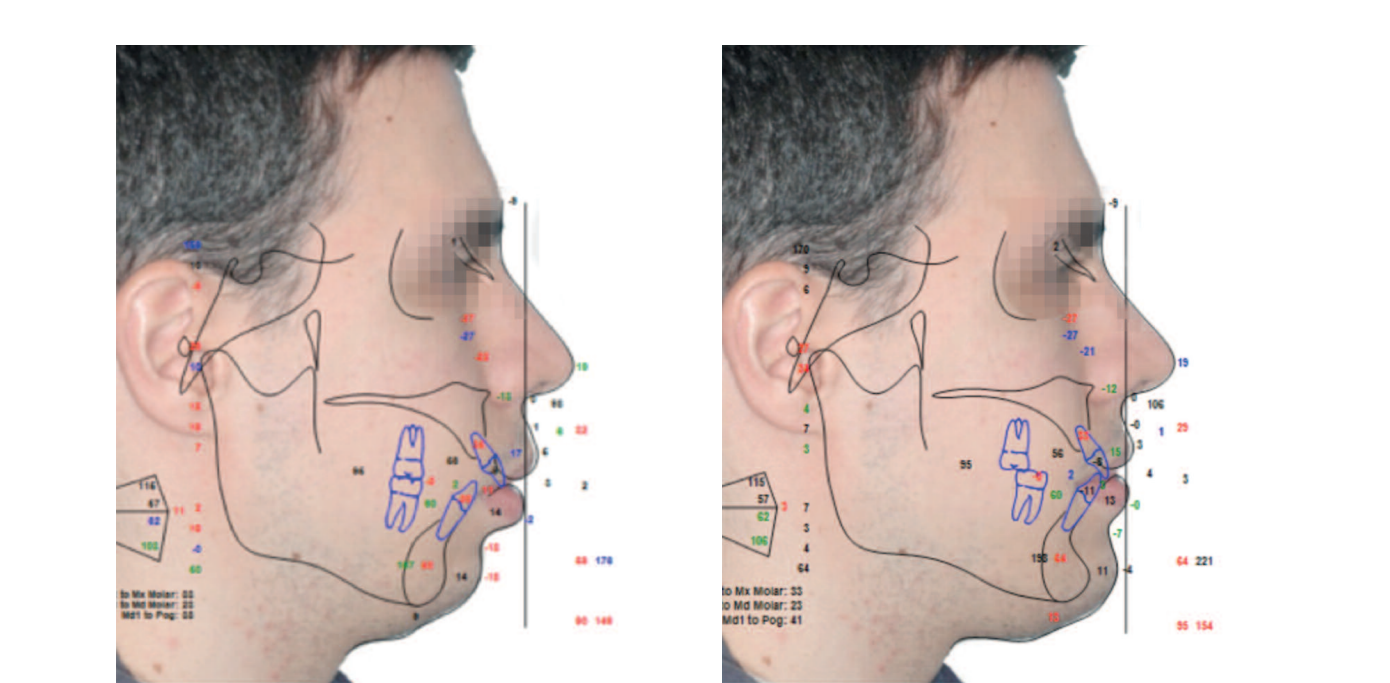

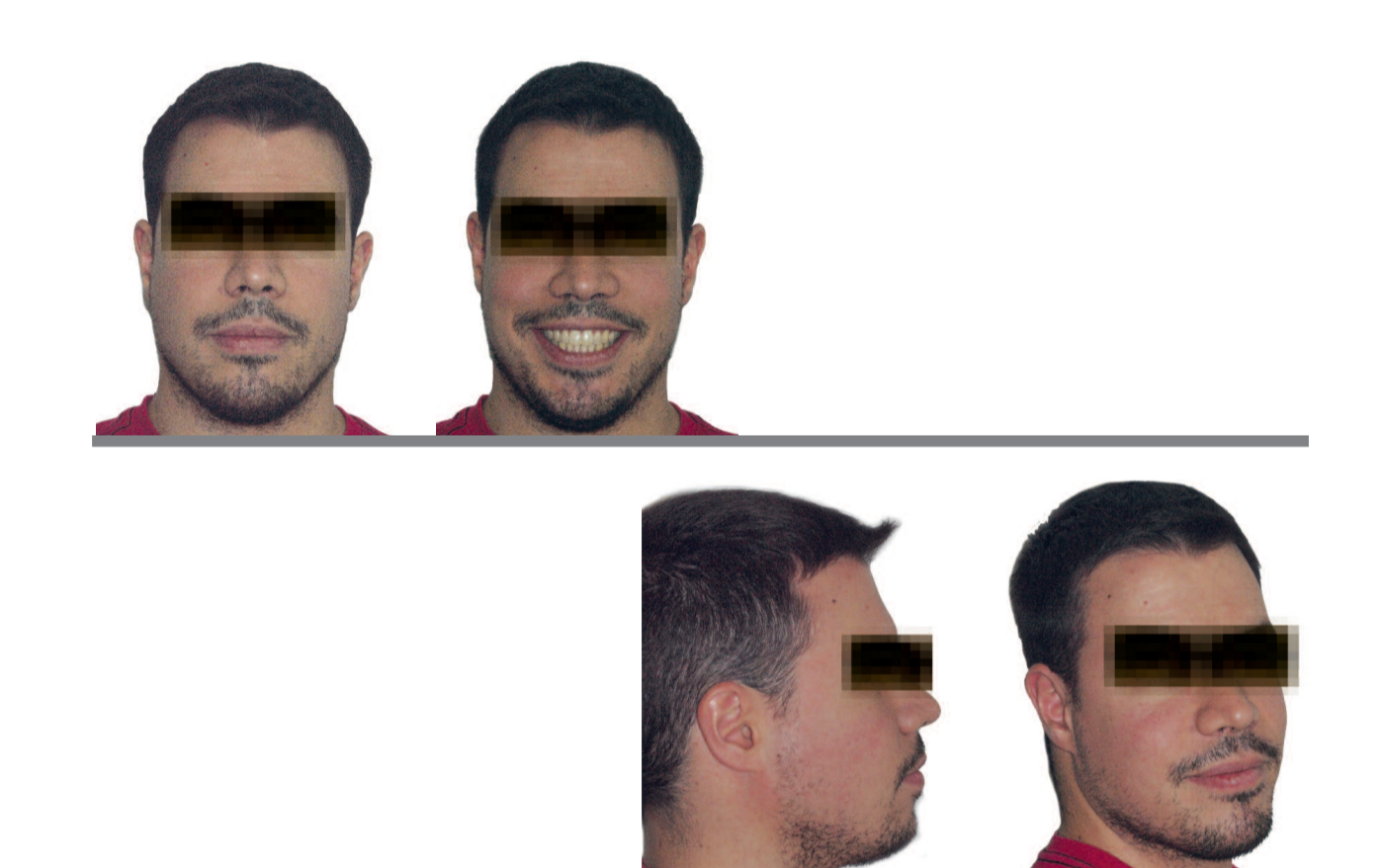

In the facial analysis (fig. 2) we detected slight maxillary vertical excess, lip incompetence, and increased gap, with excessive exposure of incisors at rest and eversion of the lower lip.

In a smiling position, the patient presents an increased lip-to-tooth relationship. The maxillary plane is leveled, and there is asymmetry in the gingival margins.

In the profile study (fig. 3), the lack of support in the lower third is observed. It is a micrognathic profile with eversion of the lower lip, decreased cervicomandibular distance, and poorly defined cervicomandibular angle, with flaccidity and double chin.

Dental Analysis

In the dental analysis (fig. 4), there is a slight posterior compression due to lack of torsion in molars and premolars; class II molar and bilateral canine; absence of overbite due to proinclination of the lower incisors; anterior crowding in both arches and multiple rotations, as well as severe proinclination of the lower incisors.

Orthodontic Plan

The orthodontic plan includes the following steps:

- Need for lower premolar extractions to retrocline the lower incisors.

- The upper incisors are slightly proclined. We will recover their position and solve the anterior crowding with stripping from canine to canine.

- Leveling of the Spee curve, intruding the lower incisors.

- Correction of the Wilson curve, with coronal vestibular torsion in upper premolars and molars.

Initial Surgical Planning

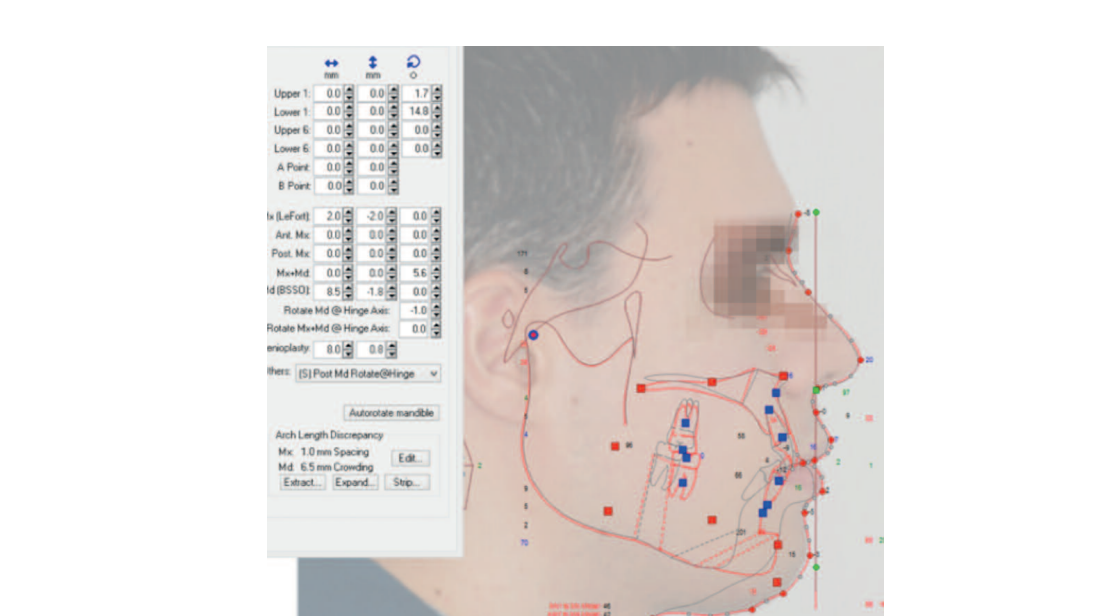

We decided to advance the maxilla by 4 mm to achieve better anteroposterior protection and, at the same time, to be able to advance the mandible to the maximum extent. The maxilla will impact vertically at its anterior part and will subsequently descend, causing the counterclockwise rotation of the occlusal plane.

Pre-surgical Situation

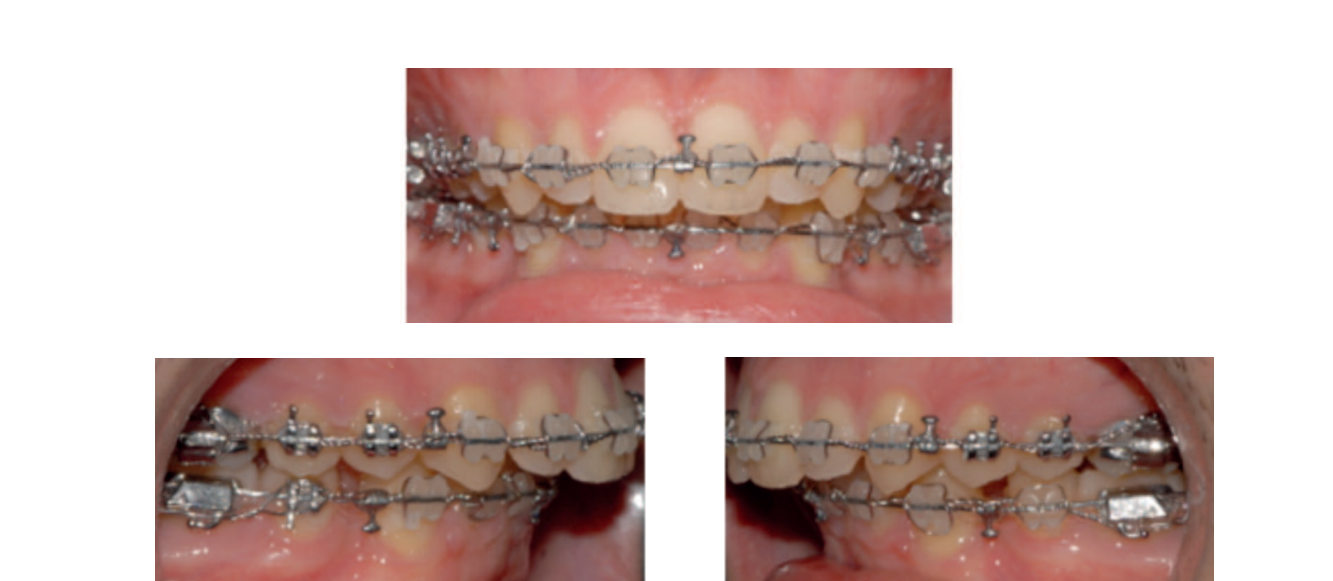

Once the lower Spee curve is leveled and the inclination of the lower incisors is corrected, our pre-surgical orthodontic goal is achieved. The loss of posterior anchorage to finish closing the extraction spaces can be left for the post-surgical phase, taking advantage of the RAP (regional acceleration phenomenon).

Bimaxillary Surgery Planning

The maxilla will be moved forward 4 mm to ensure sufficient mandibular advancement for an aesthetic mandibular projection. The final vertical position of the upper incisors will be determined at the end of the surgery, with the maxillae in occlusion and measuring from a fixed point, which is established with a self-tapping screw from the beginning of the surgery at the nasion.

The final determination of the position of the upper incisors, horizontally and vertically, significantly affects the aesthetics of the smile. The mandible will advance, and a mentoplasty for advancement and vertical augmentation will be performed.

Bimaxillary Surgery

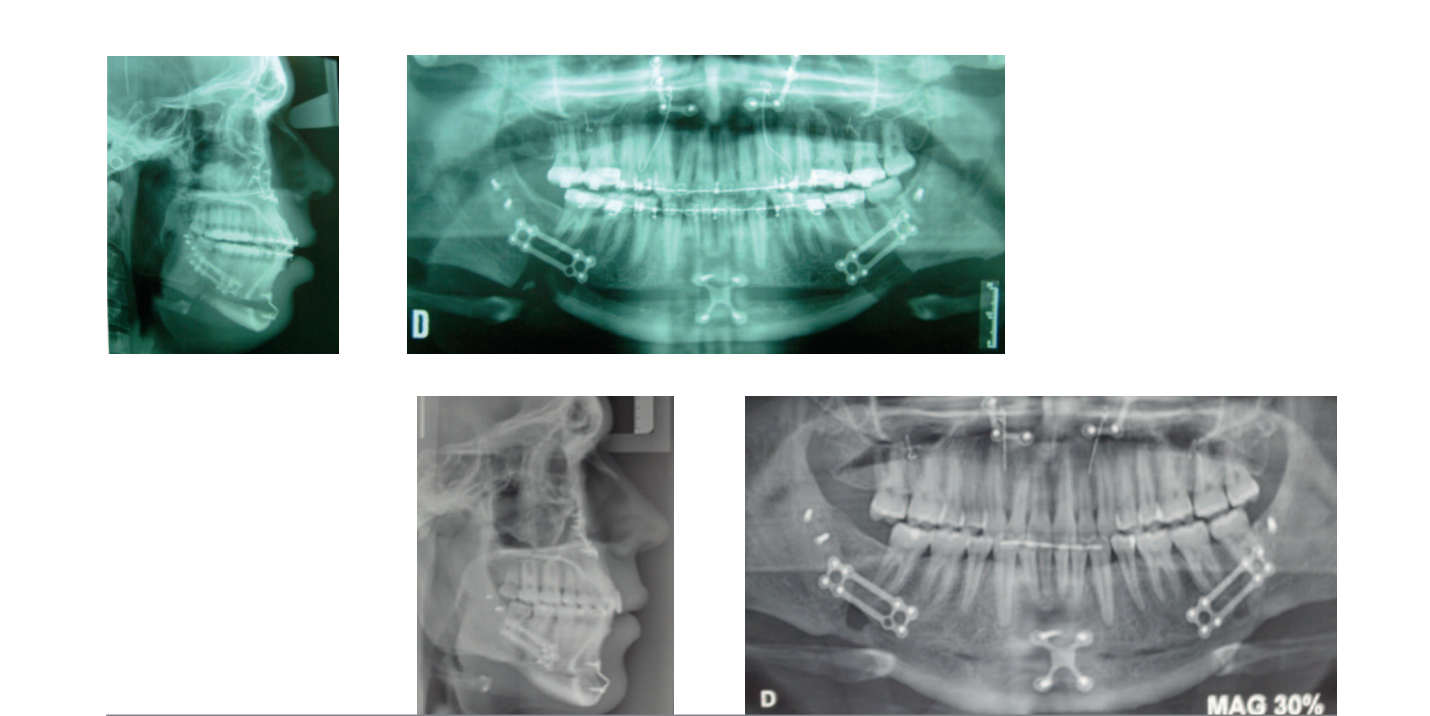

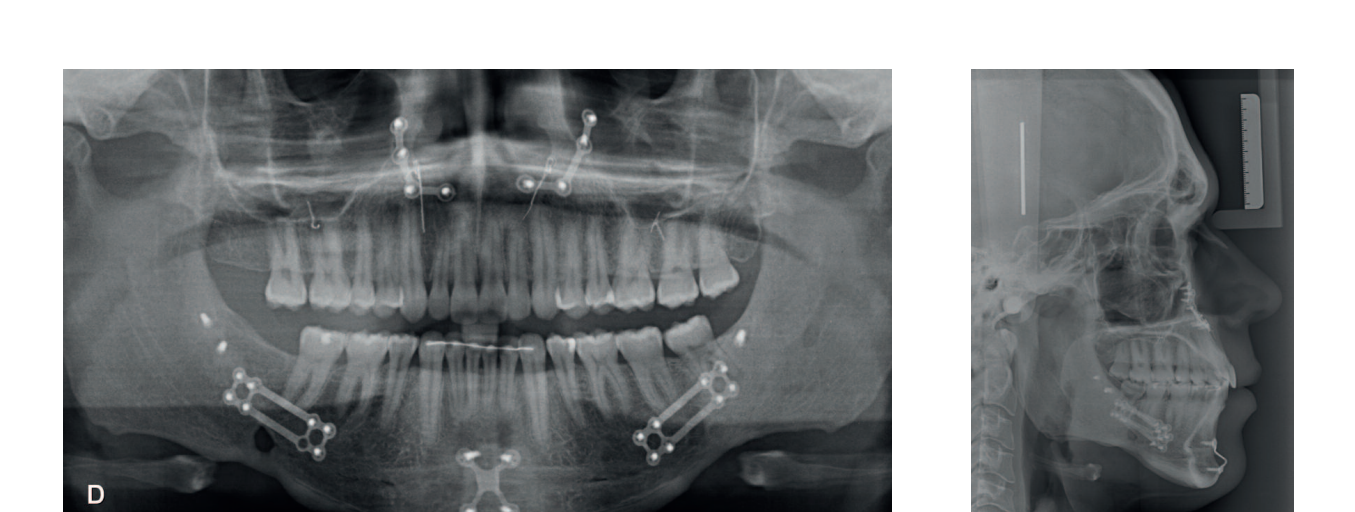

Under general anesthesia, nasotracheal intubation was performed. The surgery began with the upper jaw, performing a Lefort I osteotomy with anterior impaction of 2 mm, posterior descent of 2 mm, and advancement of 4 mm. Septoplasty and submucosal resection of turbinates were carried out.

The osteotomies were rigidly fixed with two plates in the piriform buttress and with wires in the zygomatics. Skeletal traction was used in the posterior maxilla.

The mandible was osteotomized using the Obwegeser Epker technique and advanced 14 mm. A significant detachment of the muscles of the ramus and body was performed to facilitate the advancement. The osteotomies were consistently fixed with rigid 2 mm plates with an advancement bridge. The patient remained in the ICU for 24 hours. No intermaxillary wiring was performed, and class II elastics were placed. A mentoplasty of 3 mm advancement and 6 mm descent was executed.

Completion and retention

Stability at three years post-treatment

Results

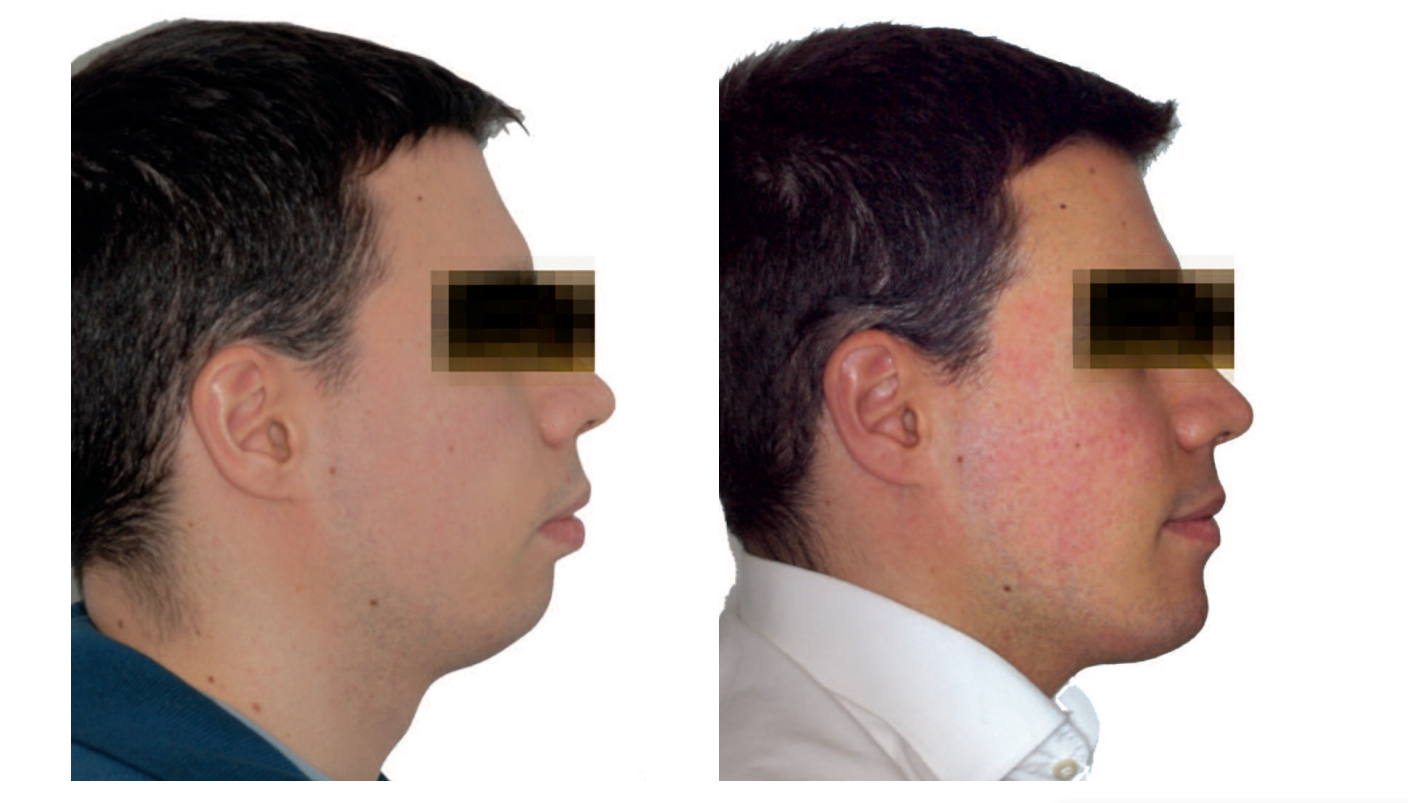

The patient is evolving satisfactorily and the obtained occlusion is stable. The facial results demonstrate a clear aesthetic improvement.

The skeletal expansion caused by the advancement of the maxillae with counterclockwise rotation and mentoplasty represents an unparalleled aesthetic improvement compared to any other type of facial surgery. The long-term changes are stable and lasting.

The skeletal expansion resulted in an improvement in the airways, as shown in the radiological overlays.

Conclusions

Dento-facial deformities affect 10-15% of the population with varying degrees of aesthetic or functional impact, which may concern only one maxilla or the entire face.

This case represents the paradigm of new changes in the way we think about orthognathic surgery. Not only is a satisfactory occlusal state achieved, but this surgery gives us the opportunity to obtain better aesthetic and functional results, which are not comparable to other surgical approaches.

Individuals with moderate deformity transform their aesthetics, and the improvements go beyond that, as there is no other technique comparable to orthognathic surgery that causes changes in the airways like bimaxillary advancement surgery with occlusal plane change. In this patient, the surgery caused skeletal expansion.

The improvement in appearance has a profound importance in how individuals judge themselves and how society observes them. It has a significant impact on self-esteem. The desire to improve appearance is notable in patients with deformity, even in those who say their motivations are functional, as it is easier to justify the need for treatment that way.

Orthognathic surgery is recommended for the treatment of most of these cases, achieving functional occlusion combined with an improvement in chewing, breathing, and phonation.

Many of our patients come for orthodontic treatment, but the professional's duty lies not only in achieving a stable occlusal goal but also in improving facial aesthetics, with all its positive psycho-emotional consequences.

César Colmenero Ruiz, Elena Bonilla Morente, Silvia Rosón Gómez, Carmen Torres de la Torre

Bibliography

- Bell WH. Revascularization and bone healing after maxillary osteotomy: a study using adult rhesus monkeys. Oral Surg. 1960; 27: 269-277.

- Brevi BC, Fuma L, Pau M, Sesena E. Counterclockwise rotation of the occlusal plane in the treatment of OSAS. J. Oral. Maxillofac Surg. 2011; 69 : 917- 923.

- Bloomquist JE, Ahlborg G, Isaakson S. A comparison of skeletal stability after mandibular advancement and use of two rigid internal fixation techniques. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1997; 55: 568-576.

- Noguchi N, Tsuji M. An orthognathic simulation system integrating teeth jaw and face data using 3D cephalometry. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2007; 36: 640-5.

- Poulto DR, Ware WH. Surgical-orthognathic treatment of severe mandibular retrusion. Am. J. Orthod. 1971; 58: 244-252.

- Sarver DM. The smile arc. The importance of incisor position in the dynamic smile. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2001; 120: 98-111.

- Swennen GRJ, Mollemans W, Schutyser F. Three-dimensional treatment planning for orthognathic surgery in the era of virtual imaging. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2007; 67: 2080-87.